+ Author Affiliations

- Correspondence to J Anton Grootegoed, Department of Reproduction and Development, Erasmus MC – University Medical Center Rotterdam, Room Ee 09-71, PO Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands; j.a.grootegoed@erasmusmc.nl

- Contributors KNB and MK designed the experiments, KNB carried out the experiments, MK provided lab equipment and test materials, all authors contributed to the data interpretation, the writing of this manuscript was led by JAG, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

- Accepted 28 March 2011

- Published Online First 3 May 2011

Abstract

Based on DNA analysis of a historical case, the authors describe how a female athlete can be unknowingly confronted with the consequences of a disorder of sex development resulting in hyperandrogenism emerging early in her sports career. In such a situation, it is harmful and confusing to question sex and gender. Exposure to either a low or high level of endogenous testosterone from puberty is a decisive factor with respect to sexual dimorphism of physical performance. Yet, measurement of testosterone is not the means by which questions of an athlete's eligibility to compete with either women or men are resolved. The authors discuss that it might be justifiable to use the circulating testosterone level as an endocrinological parameter, to try to arrive at an objective criterion in evaluating what separates women and men in sports competitions, which could prevent the initiation of complicated, lengthy and damaging sex and gender verification procedures.

Footnotes

- Note On 12 April 2011, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) announced the adoption of new rules and regulations governing the eligibility of females with hyperandrogenism to participate in women's competition, which will come into force from 1 May 2011 (http://www.iaaf.org/aboutiaaf/news/newsid=59746.html).It appears that these new IAAF rules, as announced, are in full agreement with the viewpoint expressed in our article, which at the time of the IAAF announcement was already in press with the British Journal of Sports Medicine. We would like to emphasise that our viewpoint was composed independently from IAAF, and that none of the authors has been in contact with the respective IAAF expert working group.

- Funding KNB and MK were supported by the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI), and the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) within the framework of the Forensic Genomics Consortium Netherlands (FGCN).

- Patient consent Obtained.

- Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This paper is freely available online under the BMJ Journals unlocked scheme, see http://bjsm.bmj.com/info/unlocked.dtl

Abstract

Based on DNA analysis of a historical case, the authors describe how a female athlete can be unknowingly confronted with the consequences of a disorder of sex development resulting in hyperandrogenism emerging early in her sports career. In such a situation, it is harmful and confusing to question sex and gender. Exposure to either a low or high level of endogenous testosterone from puberty is a decisive factor with respect to sexual dimorphism of physical performance. Yet, measurement of testosterone is not the means by which questions of an athlete's eligibility to compete with either women or men are resolved. The authors discuss that it might be justifiable to use the circulating testosterone level as an endocrinological parameter, to try to arrive at an objective criterion in evaluating what separates women and men in sports competitions, which could prevent the initiation of complicated, lengthy and damaging sex and gender verification procedures.

Introduction

In 1949, the Dutch track athlete Foekje Dillema (1926–2007) came to prominence on the world athletic stage. She started to rival Fanny Blankers-Koen, the world-famous Dutch track athlete who won four gold medals during the 1948 Summer Olympics in London and was elected Female Athlete of the Century by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) in 1999. In contrast, Dillema's career was of short duration, with a dramatic ending. In 1950, she was expelled for life by the Royal Dutch Athletics Federation, due to the results of a 'sex test', for which details or results were never revealed and no records are available. Her 1950 national record of 24.1 s for the 200 m, which she took from Fanny Blankers-Koen, was erased, and only after her death 57 years later was she reinstated by the Royal Dutch Athletics Federation (figure 1).1

Figure 1

Foekje Dillema (in white shirt on the left) together with Fanny Blankers-Koen, on the Olympic Day, 18 June 1950, in the Olympic Stadium, Amsterdam, when 60 000 spectators witnessed Dillema winning the 200 m in 24.1 s, in a race in which Blankers-Koen did not participate.1 Photo: Ben van Meerendonk (collection International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam).

The verification of the sex of athletes has been an issue for many decades. It should be noted that reports and reviews on this topic refer to gender verification, rather than sex verification.2,–,4 However, what counts in competitive sports is a person's sex characteristics. Trying to avoid the word sex, given its charged nature, can only cause confusion.5 6 Herein, we will use the term sex for the biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women, as compared to gender and gender identity in reference to the socially and individually perceived sexual identity of an individual from birth to puberty and adulthood.5 7 8

Sex verification in 1950 was based solely on physical examination, predating hormone assays or sex chromosome analysis. Following discovery of the Barr body in female cells in 1949, it took some 12 years before it was known that this body represents an inactivated X chromosome9; from the late 1960s its detection was used in sex verification tests in the context of sports competitions.2,–,4 Subsequent tests focused on the male-specific region of the Y chromosome, particularly the male sex determining SRY gene.10 However, opposition to sex verification for female athletes with laboratory-based genetic testing developed in the 1970s and 1980s, because these tests did not encompass the complexities of disorders of sex development (DSDs). Since the 2000 Summer Olympics, questioned sex and gender is evaluated on a case-by-case basis by a team of specialists in the areas of endocrinology, genetics, gynaecology and psychology.3,–,5

To broaden the perspective on sportswomen confronted with questioned sex characteristics, we have investigated the case of Foekje Dillema, with informed consent from her heirs, by means of DNA analysis of samples from worn clothing. Appreciating the nature of the samples tested, we applied DNA methodology and lab quality standards used in human forensics. Our DNA analysis indicates that Foekje Dillema had a 46,XX/46,XY mosaic condition with a rare origin, which we interpret as leading to hyperandrogenism from her puberty. Based on this historical case we discuss that, if a sportswoman is confronted with signs of a DSD early in her sports career, it is harmful and confusing to question such a person's sex and gender. Rather, we suggest that it is necessary to try to arrive at an objective criterion in evaluating what separates women and men in sports competitions.

Reconstruction of a historical case

From the combined genotyping and DNA quantification results, we conclude that Foekje Dillema was a 46,XX/46,XY mosaic, with equal numbers of both genetic cell types at least in her skin (online supplementary data). In the fetal gonads of a 46,XX/46,XY mosaic, the tissue ratio of XX:XY cells will push the bipotential gonads to become either ovaries or testes, or both. A preponderance of 46,XX cells in fetal gonads can lead to the development of ovaries, but with some 46,XY testis tissue present in one or both of these ovaries. Such an ovotestis condition, which can also occur in the form of a complete ovary and a complete testis on either side, has been referred to with the term true hermaphroditism.11 12 The most common karyotype found in true hermaphroditism is 46,XX, followed by 46,XX/46,XY chimerism and mosaicism.12 We would like to emphasise that the term hermaphrodite, as well as other terms such as intersex, need to be replaced by the DSDs classification proposed by consensus in 2006,13 for the simple reason that the terms hermaphrodite and intersex cannot, and should not, be applied to human individuals. Instead, a true hermaphrodite is correctly referred to as either a female or male individual with ovotesticular DSD.13 When ovotestis formation is confined to only one of the gonads, the other gonad and the ovarian part of the ovotestis can function as steroidogenic ovarian tissue.11 12 The testicular part of the fetal ovotestis will produce anti-Müllerian hormone, insulin-like factor 3 and testosterone,14 acting towards regression of Müllerian ducts, initiation of testis descent and partial virilisation by circulating androgens, respectively, but none of these effects might reach a level where overt fetal virilisation leads to the birth of a boy. Hence, an individual with ovotesticular DSD often is raised as a girl,12 and also experiences a female gender identity (described below).

The X:Y ratio in the adult skin, as we obtained from Dillema's clothes, does not provide any information about the ratio in her fetal gonads. However, Foekje Dillema was formally registered as a female at birth, and she was raised as a girl, according to all accounts, including those available from her family. Hence, she is unlikely to have been exposed to a markedly elevated level of testosterone during fetal development. From all available data, including the present DNA evidence, we deduce that Dillema had an ovotesticular DSD with a predominance of ovarian tissue. At the onset of puberty, gonadotropic stimulation of the gonads most likely led to marked activation of steroidogenesis – the production of both oestradiol and testosterone in Dillema's case of ovotesticular DSD. From photographs, it is evident that from puberty she had breast development, but personal accounts also indicate that she showed some facial hair growth.1 Hyperandrogenism from puberty may have contributed to Dillema's athletic performance.

Sex characteristics, gender identity and testosterone

To have, or not to have, a Y chromosome is the primary decisive factor in human sexual differentiation, but there are exceptions. A prominent example is offered by 46,XY females who have the complete form of androgen insensitivity syndrome (cAIS), when the testes produce testosterone but the body is not able to respond to androgens (testosterone and its more powerful metabolite dihydrotestosterone) due to mutation of the X-encoded androgen receptor.14 Consequently, these individuals are born and raised as girls, and have a female gender identity.15 16 Action of testosterone through binding to the androgen receptor in the developing fetal brain is the predominant factor in programming human male gender identity,7 17 and the female gender identity of 46,XY cAIS women is explained by loss of this androgenic effect. In sports, 46,XY cAIS women can be expected to have a disadvantage compared to 46,XX women with a functional androgen receptor, the latter profiting from stimulation of muscle strength by a low level of circulating testosterone.18 19

The biological basis for sex segregation in sports is the consequence of long-term endogenous androgen exposure of men after puberty.20 It cannot be excluded that proteins encoded by genes in the male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY)21 might act together with androgens, widening the physiological gap between women and men. However, such a role for MSY genes will be minor, compared to the predominant role of androgen action. In men, the postpubertal testosterone level is a proven dose-dependent factor when muscle strength and other physiological factors such as the blood haemoglobin level come into play.22 A moderate pubertal and postpubertal excess of testosterone in a young woman can give extra muscle development and other signs of hyperandrogenism, but it would be a rude error to even suggest that this would affect her female gender identity.

Competitive athletes exploit fortunate combinations of natural differences in physical and mental personal characteristics, including individual variation of the endogenous testosterone level. The World Anti-Doping Agency states that an athlete's sample will be found positive if the concentration of an endogenous androgenic steroid hormone is above the range normally found in humans, and is not likely consistent with normal endogenous production, unless the elevated concentration of the steroid hormone (or metabolites or markers) is attributable to a physiological or pathological condition.23 Strictly speaking, a female athlete is free to benefit from any endogenous source of androgen production. Some female athletes may benefit, probably to a small extent, from increased androgen production originating from a polycystic ovary.19 This is viewed as acceptable by the IAAF, who stated that conditions that may provide some advantages but nevertheless are acceptable include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-producing tumours and an ovulatory androgen excess associated with a polycystic ovary.24 According to these regulations, hyperandrogenism caused by ovotesticular DSD would be unacceptable only if sex and gender verification would provide evidence that the female athlete in fact is a man. However, we consider it highly unlikely that any individual would aim to participate in sports competitions in conflict with his or her gender identity. There is no problem in sports at large that warrants an examination, initiated by a sports federation, of the authenticity of an adult individual's sex and gender. Hence, there is a need to reconsider the situation.

What is already known on this topic

The complex biology of sex development and its disorders appears to preclude a swift and objective assessment of the eligibility of specific women athletes to compete with other women in competitive sports. Prominent cases, historical and recent, have suffered much confusion and resulted in lengthy procedures, harmful to both the respective athletes and to sports and society at large.

What this study adds

Describing a historical case, this study puts forward the notion that societal appreciation of sex and gender issues in highly competitive sports requires discussion and understanding of relevant biomedical knowledge. However, the authenticity of an adult individual's sex and gender identity should not be questioned. Rather, there is a need for an objective and relevant criterion in evaluating what separates women and men in sports competitions.

It might be considered to set an upper limit for the circulating total testosterone level for sportswomen. In cases of cAIS, a high testosterone level would be of no significance. In any other case where the total testosterone level is found to exceed a set limit, causes and consequences need to be resolved before the sportswoman (re-)enters sports competition. This would be ethically justifiable, given the fact that it would be in the individual's own interest to prevent symptoms of long-term hyperandrogenism. The causes and consequences of a high-testosterone level can be dealt with in private, not in public, and, most importantly, without questioning gender identity. The eligibility of Dillema to compete might still be questioned, even today in the current era of improved knowledge about DSDs. However, if an increased endogenous testosterone level would have been detected, possible treatment to lower this level would have cleared the way to competition re-entry, leaving no trace of a sex and gender discussion.

Obviously, a proper definition of an upper limit for the endogenous testosterone level will require a detailed discussion about measurement, metabolites, circadian and other variations, binding proteins, etc.25,–,27 Normative ranges have not been well established,28 but available data indicate that a circulating total testosterone level of 3–4 nmol/l normally will not be exceeded by women of younger age.18 29 Leaving all antidoping controls fighting against the use of exogenous androgens in place,30 it might be relatively straightforward to arrive at a consensus about the maximally allowed endogenous total testosterone level. With 8–12 nmol/l total testosterone being considered as a lower limit which may require substitution in men,27 and with a reference range of 11–35 nmol/l for men,31 there is a substantial and significant gap in the testosterone level between women and men.

It has been argued that sex is not a binary quantity, with the far-reaching implication that sex segregation in competitive sports is an inconsistent and unjust policy.32 This argument was substantiated by pointing out that an individual's genetic background may cause a differential sensitivity to testosterone. Indeed, a genetic polymorphism such as the CAG repeat polymorphism in exon 1 of the gene encoding the androgen receptor affects the sensitivity of cells and tissues to androgens.33 However, this effect is likely far too small34 to provide any female athlete with an advantage bringing her on par with male athletes. Such a common genetic variation should not be taken into account and does not obstruct the prevailing thought that women and men are to compete separately, meaning that there is a need for a dividing line.35 Thinking about a dividing line, there is much agreement that current principles and procedures need to be revisited.35,–,37

The historical case described herein concerns ovotesticular DSD, where the amount of steroidogenic testicular tissue will determine if the affected person develops as a woman or as a man, regarding both gender and sexual characteristics. As such, this type of DSD can be viewed as a paradigm, demonstrating that the testosterone level might offer an objective parameter to separate the sexes, if required. In fact, this parameter is already implemented, in the context of sports. Athletes (46,XY and androgen sensitive) who have undergone male-to-female sex reassignment are welcome to engage in sports competitions from 2 years after the sex change, as of the Olympic Games 2004 in Athens, according to fortunate and emancipative regulations by the International Olympic Committee.38 Similarly, athletes (46,XX and androgen sensitive) who have undergone female-to-male sex reassignment can compete, but they will receive exogenous testosterone. For female-to-male sex-reassigned individuals receiving testosterone supplementation, a total testosterone level of around 30 nmol/l has been reported.39 Perhaps, one day we may witness a talented 46,XX sex-reassigned male who is able to successfully compete with 46,XY males, thanks also to approved testosterone supplementation. Men exposed to stress and exhaustion face difficulty in maintaining their endogenous testosterone level,40,–,42 which might imply an advantage for 46,XX sex-reassigned males, particularly in endurance sports. Similarly, a therapeutic use exemption for long-term testosterone administration in 46,XY men, to compensate for a secondary loss of gonadal testosterone production, might provide an advantage. The above serves to illustrate the point that current concepts and regulations regarding the relationship between sex and testosterone in sports offer room for consideration. We feel that this should be taken as a starting point to discuss the circulating testosterone level as a relevant criterion in evaluating what separates women and men in sports competitions.

The present report is not meant to provide a guideline, which would require detailed analysis of total testosterone levels in large numbers of female and male athletes in relation to possible confounding factors, and consensus meetings. Rather, we aim to contribute to an open discussion involving experts from the fields of biology, medicine, genetics, psychology, sports and ethics, to accomplish a procedure which would respect the authenticity of an adult individual's sex and gender identity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the heirs of Foekje Dillema for their frank and considerate willingness to dedicate information and materials to the present historical perspective on female athletes confronted with questioned gender issues. For the photograph of figure 1 we obtained right of use from the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

Footnotes

- Note On 12 April 2011, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) announced the adoption of new rules and regulations governing the eligibility of females with hyperandrogenism to participate in women's competition, which will come into force from 1 May 2011 (http://www.iaaf.org/aboutiaaf/news/newsid=59746.html).It appears that these new IAAF rules, as announced, are in full agreement with the viewpoint expressed in our article, which at the time of the IAAF announcement was already in press with the British Journal of Sports Medicine. We would like to emphasise that our viewpoint was composed independently from IAAF, and that none of the authors has been in contact with the respective IAAF expert working group.

- Funding KNB and MK were supported by the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI), and the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) within the framework of the Forensic Genomics Consortium Netherlands (FGCN).

- Patient consent Obtained.

- Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This paper is freely available online under the BMJ Journals unlocked scheme, see http://bjsm.bmj.com/info/unlocked.dtl

References

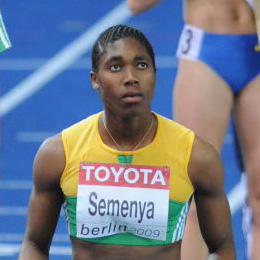

Caster Semenya

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | South African |

| Born | 7 January 1991 Pietersburg (now Polokwane) |

| Residence | South Africa |

| Alma mater | University of Pretoria |

| Height | 1.70 metres (5 ft 7 in) |

| Weight | 64 kilograms (140 lb) |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Running |

| Event(s) | 800 metres, 1500 metres |

| Achievements and titles | |

| Personal best(s) | 800m: 1:55.45 1500m: 4:08.01 |

Mokgadi Caster Semenya (born 7 January 1991) is a South African middle-distance runner and world champion.[1][2] Semenya won gold in the women's 800 metres at the 2009 World Championships with a time of 1:55.45 in the final.

Following her victory at the 2009 World Championships, it was announced that she had been subjected to gender testing.[2] She was withdrawn from international competition until 6 July 2010 when the IAAF cleared her to return to competition.[3][4] In 2010, the British magazine New Statesman included Semenya in a list of "50 People That Matter 2010".[5]

Semenya returned to the 2011 World Championships where she achieved the silver medal in the 800 metres.

Early life and education

Semenya was born in Ga-Masehlong, a village in South Africa near Pietersburg (now Polokwane), and grew up in the village of Fairlie, "deep in South Africa's northern Limpopo province."[1][6] She has three sisters and a brother, and is said to have been a tomboy as a child.[6][7]

Semenya attended Nthema Secondary School and now attends the University of Pretoria as a sports science student.[2][8] She began running as training for soccer.[9]

Career

2008

In July Semenya participated in the 2008 World Junior Championships, and won the gold in the 800 m at the 2008 Commonwealth Youth Games with a time of 2:04.23.[10]

2009

In the African Junior Championships Semenya won both the 800 m and 1500 m races with the times of 1:56.72 and 4:08.01 respectively.[11][12] With that race she improved her 800 m personal best by seven seconds in less than nine months, including four seconds in that race alone.[2][13] The 800 m time was the world leading time in 2009 at that date.[13] It was also a national record and a championship record. Semenya simultaneously beat the Senior and Junior South African records held by Zelda Pretorius at 1:58.85, and Zola Budd at 2:00.90, respectively.[14]

The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) says it was "obliged to investigate" after she made improvements of 25 seconds at 1500 m and eight seconds at 800 m – "the sort of dramatic breakthroughs that usually arouse suspicion of drug use."[15] The IAAF also asked Semenya to undergo a gender test after the win.[16][note 1] News that the IAAF requested the test broke three hours before the 2009 World Championships 800 m final.[13] IAAF president Lamine Diack stated, "There was a leak of confidentiality at some point and this led to some insensitive reactions."[17]

In August Semenya won gold in the 800 metres at the World Championships with a time of 1:55.45 in the final, again setting the fastest time of the year.[18]

Gender test

Following her victory at the world championships, questions were raised about her gender.[2][13][19][20]

The IAAF's handling of the case spurred many negative reactions. A number of athletes, including retired sprinter Michael Johnson, criticized the organization for its response to the incident.[16][21] Prominent South African civic leaders, commentators, politicians, and activists characterized the controversy as racist, as well as an affront to Semenya's privacy and human rights.[22][23] The IAAF said it only made the test public after it had already been reported in the media, denying charges of racism and expressing regret about "the allegations being made about the reasons for which these tests are being conducted."[15][24] The federation also explained that the motivation for the test was not suspected cheating but a desire to determine whether she had a "rare medical condition" giving her an unfair competitive advantage.[25] The president of the IAAF stated that the case could have been handled with more sensitivity.[26] In an interview with South African magazine YOU Semenya stated, "God made me the way I am and I accept myself." She also took part in a makeover with the magazine.[27]

On 7 September 2009, Wilfred Daniels, Semenya's coach with Athletics South Africa (ASA), resigned because he felt that ASA "did not advise Ms. Semenya properly". He apologized for personally having failed to protect her.[28] Athletics South Africa President Leonard Chuene admitted on 19 September 2009 to having subjected Semenya to gender tests. He had previously lied to Semenya about the purpose of the tests and to others about having performed the tests. He ignored a request from ASA team doctor Harold Adams to withdraw Semenya from the world championships over concerns about the need to keep her medical records confidential.[29] On the recommendation of South Africa's Minister for Sport and Recreation, Makhenkesi Stofile, Semenya retained the legal firm Dewey & LeBoeuf who are acting pro bono "to make certain that her civil and legal rights and dignity as a person are fully protected."[30][31][32] Following the furore over her gender, Semenya received great support within South Africa,[16][21] to the extent of being called a cause célèbre.[23]

In November 2009 South Africa's sports ministry issued a statement that Semenya had reached an agreement with the IAAF to keep her medal and the prize money.[33] The ministry did not say if she would be allowed to compete as a woman but they did note that the IAAF's threshold for when a female is considered ineligible to compete as a woman is unclear.[33] In December 2009 Track and Field News voted Semenya the Number One Women's 800 metre runner of the year.[34]

2010

Semenya on the 2010 Diamond League circuit

In March 2010 she was denied the opportunity to compete in the local Yellow Pages Series V Track and Field event in Stellenbosch, South Africa, because the IAAF had yet to release its findings from her gender test.[35]

On 6 July, the IAAF cleared Semenya to return to international competition. The results of the gender tests, however, will not be released for privacy reasons.[3] She returned to competition nine days later winning two minor races in Finland.[36] On August 22, 2010, running on the same track as her World Championship victory, Semenya started slowly but finished strongly, dipping under 2:00 for the first time since the controversy, while winning the ISTAF meet in Berlin.[37]

Not being on full form, she did not enter the World Junior Championships or the African Championships, both held in July 2010, and opted to target the Commonwealth Games to be held in October 2010.[38] She improved her season's best to 1:58.16 at the Notturna di Milano meeting in early September and returned to South Africa to prepare for the Commonwealth Games.[39] Eventually, she was forced to skip the games due to injury.[40]

In September, the British magazine New Statesman included Semenya in its annual list of "50 People That Matter" for unintentionally instigating "an international and often ill-tempered debate on gender politics, feminism, and race, becoming an inspiration to gender campaigners around the world."[5]

- ^ The IAAF ceased compulsory tests in 1992 but retains the right to test athletes. Scant support for sex test on champion athlete New Scientist Gender verification was dropped from Olympic sports in 1999 as the issue was delicate and scientifically complicated. The verification involves "an endocrinologist, a gynaecologist, an internal medicine expert, an expert on gender and a psychologist" and takes several weeks. This is not the first time the IAAF has asked for gender verification although generally the athletes maintain their privacy. "Caster Semenya faces sex test before she can claim victory" The Times, 19 August 2009

References

- ^ a b "Birth certificate backs SA gender". BBC News. 21 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8215112.stm. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Slot, Owen (19 August 2009). "Caster Semenya faces sex test before she can claim victory". London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/more_sport/athletics/article6802314.ece. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Semenya cleared to return to track immediately". Associated Press. 6 July 2010. http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5hMudI8ByYmbiNVB4ofKjep_IT_kQD9GPJLSO0. Retrieved 6 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Kessel, Anna (6 July 2010). "Caster Semenya may return to track this month after IAAF clearance". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/2010/jul/06/caster-semenya-iaaf-clearance. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Caster Semenya – 50 people that matter 2010". http://www.newstatesman.com/2010/09/intersex-symbol-caster-semenya. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ a b "'she wouldn't wear dresses and sounds like a man on the phone': Caster Semenya's father on his sex-riddle daughter". Daily Mail. 23 August 2009. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/worldnews/article-1208227/She-wouldnt-wear-dresses-sounds-like-man-phone-Caster-Semenyas-father-sex-riddle-daughter.html. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Abrahamson, Alan (20 August 2009). "Caster Semenya's present and future". Universal Sports. http://www.universalsports.com/ViewArticle.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=23000&ATCLID=204778766. Retrieved 30 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ SAfrican in gender flap gets gold for 800 win[dead link] 22 August 2009, By RYAN LUCAS, Associated Press Writer

- ^ Prince, Chandre (29 August 2009). "Hero Caster’s road to gold". The Times. http://www.thetimes.co.za/News/Article.aspx?id=1057364. Retrieved 30 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Young SA team strikes gold". Independent Online. 16 October 2008. http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=6&click_id=4&art_id=nw20081016164120337C414633. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Ouma, Mark (2 August 2009). "Nigerian Ogoegbunam completes a hat trick at Africa Junior Championships". AfricanAthletics.org. http://www.africanathletics.org/?p=245. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Ouma, Mark (31 July 2009). "South African teen Semenya stuns with 1:56.72 800m World lead in Bambous — African junior champs, Day 2". IAAF. http://www.iaaf.org/news/kind=100/newsid=52412.html. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Tom Fordyce (19 August 2009). "Semenya left stranded by storm". BBC Sport. http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/tomfordyce/2009/08/semenya_left_stranded_by_storm.html. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ South African teen Semenya stuns with 1:56.72 800m World lead in Bambous – African junior champs, Day 2 IAAF, 31 July 2009

- ^ a b Caster Semenya row: 'Who are white people to question the makeup of an African girl? It is racism': The decision to subject the gold medal-winning athlete Caster Semenya to sex tests over claims Caster is a man has provoked outrage in her village and throughout South Africa David Smith, The Observer, 23 August 2009

- ^ a b c "Semenya dismissive of gender row". BBC Sport. 20 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/athletics/8212078.stm. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Hart, Simon (24 August 2009). "World Athletics: Caster Semenya tests 'show high testosterone levels'". London: The Times. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/athletics/6078171/World-Athletics-Caster-Semenya-tests-show-high-testosterone-levels.html. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "800 Metres Women Final Results". 19 August 2009. http://berlin.iaaf.org/documents/pdf/3658/AT-800-W-f--1--.RS1.pdf. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Women's world champion Semenya faces gender test CNN, 20 August 2009

- ^ "Semenya told to take gender test". BBC Sport. 19 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/athletics/8210471.stm. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ a b "South African unite behind gender row athlete". BBC News. 20 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/8212835.stm. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn (26 August 2009). "Caster Semenya, South African runner subjected to gender test, gets tumultuous welcome home". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-fg-africa-runner26-2009aug26,0,4216318.story. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b Sawer, Patrick; Berger, Sebastian (23 August 2009). "Gender row over Caster Semenya makes athlete into a South African cause celebre". London: The Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/southafrica/6073980/Gender-row-over-Caster-Semenya-makes-athlete-into-a-South-African-cause-celebre.html. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ SA to take up Semenya case with UN[dead link] The Times SA, 21 August 2009

- ^ "SA fury over athlete gender test". BBC Sport. 20 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/8211319.stm. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "New twist in Semenya gender saga". BBC Sport. 25 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/athletics/8219937.stm. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Makeover for SA gender-row runner". BBC News. 8 September 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/8243553.stm. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "S. Africa gender row coach resigns". BBC News. 7 September 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8242060.stm. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Serena Chaudhry (19 September 2009). "South Africa athletics chief admits lying about Semenya tests". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/sportsNews/idUSTRE58I0N320090919. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Dewey takes up Semenya case in IAAF dispute – Legalweek Magazine

- ^ Dewey & LeBoeuf to advise Caster Semenya[dead link] – Times Online

- ^ Dewey & LeBoeuf Retained to Protect Rights of South African Runner Caster Semenya – press release from Dewey & LeBoeuf.

- ^ a b Jere Longman "South African Runner’s Sex-Verification Result Won’t Be Public" New York Times, 19 November 2009

- ^ Track and Field News, 22 December 2009 Vol 8 Number 59

- ^ "Semenya announces return to competitive running". NBC Sports. http://nbcsports.msnbc.com/id/36083164/. Retrieved 30 March 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Yahoo News, July 18, 2010: Semenya easily wins again in Finland[dead link]

- ^ AP article[dead link]

- ^ CBC, July 21, 2010: Semenya has eyes on Commonwealth Games

- ^ Sampaolo, Diego (2010-09-10). Howe, Semenya, and Yenew highlight in Milan. IAAF. Retrieved on 2010-09-10.

- ^ The Hindu, September 29, 2010: Injured Semenya pulls out of Commonwealth Games

External links

- IAAF profile for Caster Semenya

- Interview with Semenya after the 2009 World Championship 800 m Semi-final Part 1, Part 2 YouTube

- "Where's the Rulebook for Sex Verification?", New York Times, 21 August 2009 (Retrieved 31 January 2010)

Gender verification in sports (also known as sex verification, or loosely as gender determination or a sex test) is the issue of verifying the eligibility of an athlete to compete in a sporting event that is limited to a single sex. The issue arose a number of times in the Olympic games where it was alleged that male athletes attempted to compete as women in order to win, or that an intersexed person competed as a woman. The first mandatory sex test issued by the IAAF for woman athletes was in July 1950 in the month before the European Championships in Belgium. All athletes were tested in their own countries.[1] Sex testing at the games began at the 1966 European Athletics Championships in response to suspicion that several of the best women athletes from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe were actually men.[2] At the Olympics, testing was introduced at the 1968 Olympic Winter Games in Grenoble. While it arose primarily from the Olympic Games, gender verification affects any sporting event. However, it most often becomes an issue in elite international competition.

While it would seem a simple case of checking for XX vs. XY chromosomes to determine whether an athlete is a woman or a man, it is not that simple. Fetuses start out as undifferentiated, and the Y chromosome turns on a variety of hormones that differentiate the baby as a male. Sometimes this does not occur, and XX people with two X chromosomes can develop hormonally as a male, and XY people with an X and a Y can develop hormonally as a female.[3]

Nowadays, gender verification tests typically involve evaluation by gynecologists, endocrinologists, psychologists, and internal medicine specialists.

A commentary published in the Journal of the American Medical Association stated,

Newer rules permit transsexual athletes to compete in the Olympics after having completed sex reassignment surgery, being legally recognized as a member of the sex they wish to compete as, and having undergone two years of hormonal therapy (unless they transitioned before puberty).[7] These controversies continued with the 2008 Olympic games in Beijing.[8]

The International Association of Athletics Federations ceased sex screening for all athletes in 1992,[9] but retains the option of assessing the sex of a participant should suspicions arise. This was invoked most recently in August 2009 with the mandated testing of South African athlete Caster Semenya.[10]

The Olympic Council of Asia continues the practice.[citation needed]

While it would seem a simple case of checking for XX vs. XY chromosomes to determine whether an athlete is a woman or a man, it is not that simple. Fetuses start out as undifferentiated, and the Y chromosome turns on a variety of hormones that differentiate the baby as a male. Sometimes this does not occur, and XX people with two X chromosomes can develop hormonally as a male, and XY people with an X and a Y can develop hormonally as a female.[3]

Tests

For a period of time these tests were mandatory for female athletes. A New York Times article[clarification needed] suggests it was due to fears that male athletes would pose as female athletes and have an unfair advantage over their competitors.Nowadays, gender verification tests typically involve evaluation by gynecologists, endocrinologists, psychologists, and internal medicine specialists.

History

United States Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage requested, during or shortly after the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, that a system be established to examine female athletes. According to a Time magazine article about hermaphrodites, Brundage felt the need to clarify "sex ambiguities" after observing the performance of Czechoslovak runner and jumper Zdenka Koubkova and English shotputter and javelin thrower Mary Edith Louise Weston. Both individuals later had sex change surgery and legally changed their names, to Zdenek Koubek and Mark Weston, respectively.[4]- Perhaps the earliest known case is that of Stanisława Walasiewicz (aka Stella Walsh), a Polish athlete who won a gold medal in the women's 100 m at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, but who after her death in 1980 was discovered to have had partially developed male genitalia. (See below for genitalia as indicators of a person's sex.)

- Another Polish athlete Ewa Kłobukowska, who won the gold medal in women's 4x100 m relay and the bronze medal in women's 100 m sprint at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, is the first athlete to fail a gender test in 1967. She was found to have a rare genetic condition which gave her no advantage over other athletes, but was nonetheless banned from competing in Olympic and professional sports.

- Eight athletes failed the tests at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics but were all cleared by subsequent physical examinations.

- In 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, Princess Anne of the United Kingdom was the only female competitor not to have to submit to a sex test. She was a member of her country's equestrian team.

Controversies

The practice has come under fire from those who feel that the testing is humiliating, socially insensitive, and not entirely accurate or effective. The testing is especially difficult and problematic in the case of people who could be considered intersexual. Genetic differences can allow a person to have a male genetic make-up and female anatomy or body chemistry.A commentary published in the Journal of the American Medical Association stated,

"Gender verification tests are difficult, expensive, and potentially inaccurate. Furthermore, these tests fail to exclude all potential impostors (eg, some 46,XX males), are discriminatory against women with disorders of sexual development, and may have shattering consequences for athletes who 'fail' a test." [5]The article also states:

"Gender verification has long been criticized by geneticists, endocrinologists, and others in the medical community. One major problem was unfairly excluding women who had a birth defect involving gonads and external genitalia (i.e., male pseudohermaphroditism). ...

A second problem is that only women, not men, were subjected to Gender verification testing. Systematic follow-up was rarely available for athletes "failing" the test, which often was performed under very public circumstances. Follow-up was crucial because the subjects were not male impostors, but intersexed individuals." [5]

Current status

Sex testing has been done as recently as the Atlanta Olympic games in 1996, but is no longer practiced, having been officially stopped by the International Olympic Committee in 1999. This followed a resolution passed at the 1996 International Olympic Committee (IOC) World Conference on Women and Health "to discontinue the current process of gender verification during the Olympic Games." In individual cases the IOC stills holds on to the right to test on gender.[6]Newer rules permit transsexual athletes to compete in the Olympics after having completed sex reassignment surgery, being legally recognized as a member of the sex they wish to compete as, and having undergone two years of hormonal therapy (unless they transitioned before puberty).[7] These controversies continued with the 2008 Olympic games in Beijing.[8]

The International Association of Athletics Federations ceased sex screening for all athletes in 1992,[9] but retains the option of assessing the sex of a participant should suspicions arise. This was invoked most recently in August 2009 with the mandated testing of South African athlete Caster Semenya.[10]

The Olympic Council of Asia continues the practice.[citation needed]

Notable incidents

- Prior to the advent of sexual verification tests, German athlete Dora Ratjen competed in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and placed fourth in the women's high jump. She later competed and set a world record for the women's high jump at the 1938 European Championships before tests by the German police concluded that she was actually a man who then took the name Heinrich Ratjen.

- The Dutch sprinter Foekje Dillema was expelled from the 1950 national team after she refused a mandatory sex test in July 1950; later investigations revealed a Y-chromosome in her body cells, and the analysis showed that she probably was a 46,XX/46,XY mosaic female.[11]

- Sisters Tamara and Irina Press won five track and field Olympic gold medals for the Soviet Union and set 26 world records in the 1960s. They ended their careers before the introduction of gender testing in 1966. There is no proof of a disorder in sexual development in these cases.[2]

- Professional tennis player Renée Richards, a transsexual woman, was barred from playing as a woman at the 1976 US Open unless she submitted to chromosome testing. She sued the United States Tennis Association and in 1977 won the right to play as a woman without submitting to testing.[12]

- Indian middle-distance runner Santhi Soundarajan, who won the silver medal in 800 m at the 2006 Asian Games in Doha, Qatar, failed the gender verification test and was stripped of her medal.

- South African runner Caster Semenya won the 800 meters at the 2009 World Championships in Athletics in Berlin. The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), track and field's governing body, confirmed that Semenya had agreed to a sex-testing process that began in South Africa and would continue in Germany. On July 6, 2010, the IAAF confirmed that Semenya was cleared to continue competing as a woman, although the results of the gender testing were never officially released for privacy reasons.[13]

See also

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b R. Peel, "Eve’s Rib - Searching for the Biological Roots of Sex Differences", Crown Publishers, New York, 1994, ISBN 0-517-59298-3

- ^ Dreger, Alice (August 21, 2009). "Where’s the Rulebook for Sex Verification?". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/22/sports/22runner.html?em. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ [2] "Change of Sex" 24 August 1936 Time

- ^ a b J.L. Simpson et al., "Gender Verification in the Olympics", JAMA (2000) vol.284; pp.1568-1569.

- ^ K. Mascagni, "World conference on women and sport", Olympic Review XXVI. vol. 12, pp. 23-31, 1996-1997

- ^ If a man has a sex change, can he compete in the Olympics as a woman? The Straight Dope 22 August 2008

- ^ A Lab is Set to Test the Gender of Some Female Athletes. New York Times 30 July 2008 [3]

- ^ Simpson, JL; Ljungqvist A, de la Chapelle A, Ferguson-Smith MA, Genel M, Carlson AS, Ehrhardt AA, Ferris E. (November 1993). "Gender verification in competitive sports.". Sports Medicine 16 (5): 305–315. DOI:10.2165/00007256-199316050-00002. PMID 8272686. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8272686. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "Semenya told to take gender test". BBC Sport. 19 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/athletics/8210471.stm. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ Ballantyne KN, Kayser M, Grootegoed JA (May 2011), 'Sex and gender issues in competitive sports: investigation of a historical case leads to a new viewpoint', British Journal of Sports Medicine, doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.082552 (http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2011/05/03/bjsm.2010.082552.long)

- ^ Amdur, Neil (August 17, 1977). "Renee Richards Ruled Eligible for U.S. Open; Ruling Makes Renee Richards Eligible to Qualify for U.S. Open". The New York Times.

- ^ Motshegwa, Lesogo; Gerald Imray (07-06-2010). "World champ Semenya cleared to return to track". Associated Press. http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20100706/ap_on_sp_ot/ath_semenya_cleared. Retrieved 2010-07-06.[dead link]

External links

- Olympics Sex Test: Why the Olympic sex test is outmoded, unnecessary and even harmful, Peak Performance online

- International Olympic Committee Announces New Rules on Hyperandrogenism, The Global Herald

No comments:

Post a Comment